Career paths and career ladders are two traditional methods by which an employee can develop and progress within an organization. Career ladders are the progression of jobs in an organization’s specific occupational fields ranked from highest to lowest based on level of responsibility and pay. Career paths encompass varied forms of career progression, including the traditional vertical career ladders, dual career ladders, horizontal career lattices, career progression outside the organization and encore careers.

Employees are generally more engaged when they believe that their employer is concerned about their growth and provides avenues to reach individual career goals while fulfilling the company’s mission. A career development path provides employees with an ongoing mechanism to enhance their skills and knowledge that can lead to mastery of their current jobs, promotions and transfers to new or different positions. Implementing career paths may also have a direct impact on the entire organization by improving morale, career satisfaction, motivation, productivity, and responsiveness in meeting departmental and organizational objectives.

In the early part of the 20th century, career choice and career progression were dictated by tradition, socio-economic status, family and gender. For most men, career choice—and status within those careers—was determined by what their fathers and other male family members had done before them. For women, the career choice options were even more limited by convention and social mores. Career progression and career ladders were almost nonexistent.

In the immediate post-WWII world, the corporate organization became the driving force in U.S. business. Both employers and employees operated under an implied contract: Employees would be loyal, and in turn, employers would provide employment until retirement.

In the latter part of the 20th century, however, this traditional trajectory of a person’s career at one employer became a thing of the past. From the late 1970s onward, the U.S. economy experienced several boom-and-bust cycles, causing many organizations to undergo massive layoffs and restructuring, and to be reticent to re-staff at pre-bust levels even when times were good. Also during this period, the shift away from a manufacturing to a knowledge economy caused a decline in union membership, further diminishing the once-implied contract of employee loyalty for lifetime employment. The organizational structure became much flatter, reducing or eliminating middle management layers. To get ahead or to make more money, employees often had to look elsewhere.

Thus, a new paradigm emerged in which individuals are in charge of their ladder, where they place it, how long they leave it in place and how high they want to go on it. Traditional career ladders still exist in the 21st century, but they operate in an environment where:

- The labor force sees continuous, dramatic changes.

- The way work is organized and performed continuously evolves and changes.

- Traditional career paths will continue to wane.

- Jobs are broken down into elements, which are then outsourced.

- Employees are working alongside a nonemployee workforce that does not have career paths or logical career progressions and may be harder to motivate.

- Workers value job enrichment, flexibility and career development more than job security and stability.

- Work is redesigned to accommodate increased demands for flexibility, where employees want the choice to work from wherever and whenever they want.

Many factors influence the need for an organization to embrace formal career paths and career ladders, including:

- Inability to find, recruit and place the right people in the right jobs.

- Employee disengagement.

- Employee demands for greater workplace flexibility.

- Lack of diversity at the top.

- A multigenerational workforce.

- Limited opportunity for advancement in flatter or smaller organizations.

- Organizational culture change.

Perhaps the biggest selling point to executives for creating formal career paths and ladders is the talent crunch.

A 2021 Verizon survey conducted with 2,001 female U.S. workers found 62 percent who plan to re-enter the workforce after the pandemic said they will look for a position in a field that offers more opportunity for skills development and advancement.

MAKING EMPLOYEE DEVELOPMENT A PRIORITY

Although most CEOs understand the importance of employee development, most admit that they do not devote the necessary time and resources to this activity. In a study by global staffing firm Randstad, 73 percent of employers said fostering employee development is important, but only 49 percent of employees said leadership is adhering to this practice.

Most organizations could benefit by increasing efforts to establish clear strategies for how talent will be grown from within. Career paths and ladders can be effective strategic tools for achieving positive organizational outcomes. They can be a means to ensure an organization’s continuing growth and productivity.

BENEFITS TO THE ORGANIZATION

Aligning the employee’s career goals with the strategic goals of the organization not only helps the organization achieve its goals but also helps the organization in the following ways:

Differentiate itself from labor market competitors. Research by WorldatWork shows that organizations that do not invest in training and development of their human capital lose valuable employees to their competition. Employers can easily differentiate themselves from competitors by investing in their employees’ career development. Even a relatively small employer investment has a positive impact on loyalty.

Retain key workers. Managing employee perceptions of career development opportunities is a key to enhancing engagement and loyalty among employees. Organizations should identify workers who are central to the execution of business strategy and then develop or update retention plans to meet the needs and expectations of these employees. Critical workers include those who drive a disproportionate share of key business outcomes, significantly influence an organization’s value chain or are in short supply in the labor market. Providing identifiable career paths is an important aspect of retention plans, along with coaching and mentoring employees with high potential and moving proven performers into new roles that fit skills developed over time.

Keep younger workers. Employees’ views of work and growth opportunities vary by generation. For example, Generation Y workers (those born between 1981 and 1996) are the least likely to be interested in pay increases and most likely to be interested in learning new skills. They are also more likely to value a career path than any other generation. Randstad also found that high percentages of Generations Y and X (those born between 1965 and 1980) want pathways to personal growth. See Generation Z Seeks Guidance in the Workplace.

Decrease turnover after an economic downturn. When the economy recovers from a downturn, employers should be concerned about losing critical and high-potential talent. A spike in voluntary turnover typically occurs after a recession, and we’re experiencing it during the COVID-19 pandemic as well. The cost of voluntary turnover can be significant, and it includes loss of productivity, lost institutional knowledge and relationships, and added burdens on employees who must pick up the slack.

A July 2021 poll conducted by Monster found that:

- 86% of workers feel that their career has stalled during the pandemic.

- 79% feel pressure to push their careers further as the pandemic ends.

- 29% of workers named lack of growth opportunities as their reason for wanting to quit.

- 80% of workers do not think their current employer offers growth opportunities.

- 49% of workers expect their employer to play a part in career development.

Experts say that employees who believe their employers make effective use of their talents and abilities are overwhelmingly more committed to staying on the job.

HR professionals have new and varied roles to play in developing and implementing career paths.

HR professionals no longer have a captive base of employees with control over their climb up the ladder. Additionally, HR is no longer able to promise a position on the ladder, or a climb to the top. Recognizing that there is a new paradigm for career progression in the 21st century, HR should encourage employees to take control of their own ladders. Though an organization can provide resources and tools to assist employees in developing their skills and abilities, the organization is no longer the sole option that employees have.

The challenge to HR is not only to continue to provide career opportunities to employees but also to provide job enhancement and job enlargement opportunities. Training and development should be focused on preparing the employee for a lifetime of employability versus a lifetime of company employment.

The ambition and drive to follow that path belongs to each individual, but the guidance and support needed to navigate the way comes from managers. Managers are responsible for incorporating the organization’s definition of success into employee feedback, evaluations and development plans. Helping managers develop career paths for their employees is another area in which HR professionals can take the lead. HR professionals should help managers view employees not as their exclusive resources but as organizational resources. When managers think this way, they are more apt to encourage employees to develop themselves in areas outside their existing departments to the benefit of the entire organization. When employees move up internal career ladders through internal promotions, HR can contribute to the process of moving an employee up the career ladder by:

- Establishing fair, workable and consistently administered promotion policies and procedures. This includes establishing policies for posting—or not posting—available positions and the content and timing of promotion announcements.

- Facilitating promotions within their organizations by providing employees with career coaching, helping managers develop clear selection criteria and cushioning the blow for those not selected for promotion.

- Helping newly promoted employees make a smooth transition.

- Helping nonselected candidates continue to strengthen their skills in expectation of future opportunities within the organization.

- Although HR professionals have many responsibilities related to designing and implementing career paths and methods for employees to grow and advance, they must also receive guidance themselves in navigating and advancing their own careers.

Developing Traditional Career Paths and Ladders

Corporate-wide initiatives around career planning can be as simple as role-playing with managers on how to discuss career interests or use career mapping with their employees. More complex initiatives involve developing formal career paths for all positions within the organization. Traditional career ladders are based on the assumption that the individual wishes to continue to climb the ladder as long as he or she is able to and that the employer continues to provide opportunities.

CAREER MAPPING

A tool that managers and HR professionals can use during career planning discussions with employees is career mapping. Career maps help employees think strategically about their career paths and how to meet their career goals within the organization rather than leave it to move ahead.

Career mapping involves three steps:

- Self-assessment. A manager engages with the employee to explore his or her knowledge, skills and abilities, as well as past experiences, accomplishments and interests.

- Individualized career map. Creating an individualized career map involves identifying other positions within the organization that meet the employee’s interests. The position may be a lateral move into a different job family or a promotion. In either case, the position should capitalize on the employee’s past experiences, interests and motivation while at the same time requiring the employee to develop a certain degree of new knowledge, skills and abilities (KSAs) to give him or her something to work toward and stay engaged.

- Exploring other opportunities. The final step in career mapping is to explore other job opportunities within the organization as they become available.

For managers and employees to successfully practice career mapping, HR must develop the necessary resources to facilitate the process.

TRADITIONAL CAREER LADDERS AND CAREER ADVANCEMENT STRATEGIES

In a traditional career ladder system, the person is hired and, through a combination of experience, education and opportunity, is promoted to levels that encompass additional responsibility and concomitant compensation. This progression within an organization continues until the individual leaves the employer for another opportunity, retires, reaches a level at which no further promotional opportunities exist, chooses to decline subsequent promotional opportunities or is terminated.

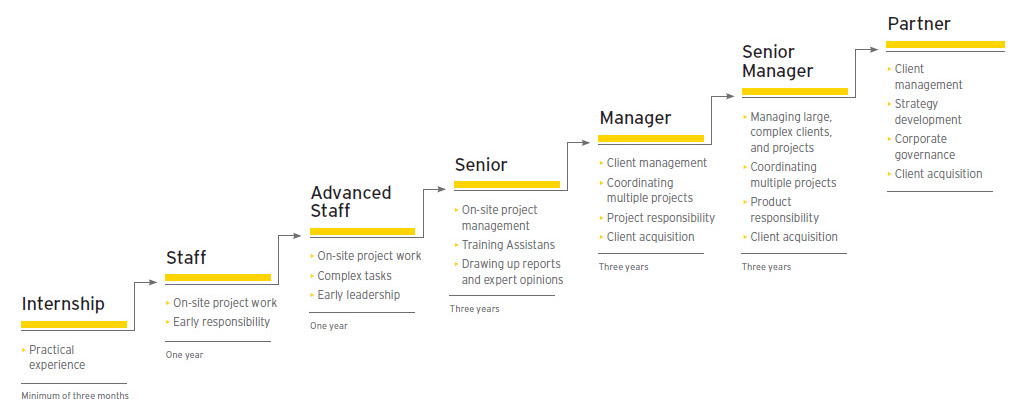

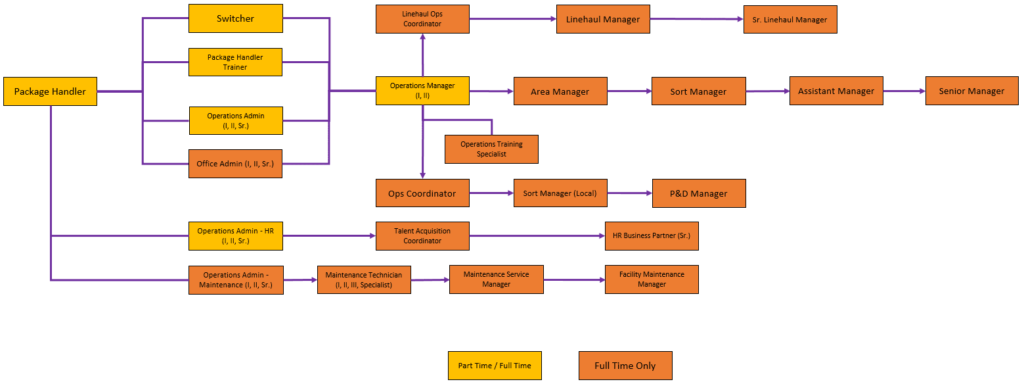

Bowling Green State University’s Business Career Accelerator program examples of career paths, including these attributed to EY and FedEx:

EY Career Ladder

FedEx Ground Career Paths

A report from Catalyst shed light on the effectiveness of various career strategies. The report suggested that career advancement requires that individuals do “all the right things” to get ahead. “Ideal workers” are those who:

- Seek high-profile assignments.

- Rub shoulders with influential leaders.

- Communicate openly and directly about career aspirations.

- Seek visibility for their accomplishments.

- Let their supervisors know of their skills and willingness to contribute.

- Seek opportunities continually.

- Learn the political landscape or unwritten rules of the organization.

- Are not afraid to ask for help.

COMMON CHALLENGES WITH TRADITIONAL LADDERS AND PATHS

Within a traditional career ladder, several issues are likely to arise, including the following.

To manage or not to manage. In many organizations, the first of several steps on an individual’s career ladder is that of an individual contributor. An inherent difficulty in many organizations, however, is that once a person reaches the level of the most experienced individual contributor, he or she must move into first-line supervision to “get ahead.” If the individual is interested in making this next step and is capable of gaining supervisory and management competencies, this progression is fine. If, however, the person does not want to move into management but still wants to receive additional compensation, then there is a problem. When this situation occurs, a typical reaction is for the individual to seek employment outside the company to earn more money. Obviously, if the person is a strong performer, this move is not to the organization’s advantage. In response to this scenario, some employers have developed dual career tracks, which are discussed in the next section of this article.

In the traditional career ladder organization, individuals may be pushed into management without the desire or the skill to do the job. Not only does the individual become frustrated with new challenges for which he or she is ill-equipped, but the organization is frustrated because it has someone in a position who is not working to potential.

No desire to climb. For some individuals, the rung at which they enter an organization is the rung at which they desire to stay. Someone who is happy at his or her current level does not aspire to advance and is a solid performer should not be pressured to climb the ladder. Encouraging supervisors to have periodic career discussions with employees is important to evaluate the current and future aspirations of all employees and will help identify those who would like to remain in their positions and those who are looking for the next step on their career ladders.

Obstacles. Career plateaus and career stagnation can also occur in the traditional career ladder and can block a person’s ability to climb the ladder. A career plateau occurs when employees reach a level in an organization in which they are either perceived to have reached their limit of progression or the organization does not provide for opportunities for future advancement. This situation may cause the employee to look outside the company for other, higher-level opportunities. Career stagnation occurs when a person is no longer psychologically engaged in his or her or job and, consequently, becomes less effective. A person who has experienced a career plateau may encounter stagnation if he or she does not actively do something to move off the plateau.

Nontraditional Methods of Career Progression

When organizations are unable to advance all employees up traditional career ladders due to low turnover, limited growth or financial constraints, other kinds of development opportunities offer ways to retain and engage employees, including job redesign, job rotation, dual career ladders, horizontal career paths, accelerated and “dialed down” career paths, and encore career paths.

JOB REDESIGN

As organizations have experienced downsizing, new technologies and demographic changes, the result has been flatter organizations that provide less opportunity for career advancement via promotions. Job redesign is an important ingredient in continuing to challenge employees to do their best work.

Job redesign can provide increased challenges and opportunities for employees to get more out of their jobs while staying on the same rung of their ladders. Commonly used job redesign strategies are job enlargement and job enrichment.

Job enlargement involves broadening the scope of a job by varying the number of different tasks to be performed. Job enrichment involves increasing the depth of the role by adding employee responsibility for planning, organizing and controlling tasks of the job.

These strategies can be used to add variety and challenge to a job while also allowing the individual to learn new skills and to further refine and develop existing skills to better prepare for advancement opportunities when they do occur. However, when jobs are enlarged but not enriched, motivational benefits are unlikely. Although the distinction between job enlargement and enrichment is fairly straightforward, employees may not correctly perceive the changes as enrichment or as enlargement.

JOB ROTATION

Job rotation is an effective method to provide job enrichment from an employee’s perspective. It involves the systematic movement of employees from job to job within an organization. Typically, formal job rotation programs offer customized assignments to promising employees in an effort to give them a view of the entire business. Assignments usually run for a year or more. Rotation programs can vary in size and formality, depending on the organization.

Job rotations are not new, but they can be highly effective. Low-level workers in job rotations can gain variety and perspective, so they do not get bored. For managers, rotations are typically designed to broaden their expertise and make them better prepared to move to the next level. As middle management jobs have disappeared in recent years, rotations for managers have become more important.

But there is a downside to job rotation programs. Such programs may increase the workload and decrease productivity for the rotating employee and for other employees who must take up the slack. In addition, line managers may be resistant to high-performing employees participating in job rotation programs. Finally, costs are associated with the learning curve on new jobs.

Preparation is a key to the success of any job rotation program. By carefully analyzing feasibility, anticipating implementation issues, communicating with and ensuring the support of senior and line managers, and setting up realistic schedules for each position, both large and small organizations can derive value from a job rotation program.

DUAL CAREER LADDERS

A dual career ladder is a career development plan that allows upward mobility for employees without requiring that they be placed into supervisory or managerial positions. This type of program has typically served as a way to advance employees who may have particular technical skills or education but who are not interested or suited to management. The following is an example of a dual career ladder, as provided by TalentAlign OD:

Advantages of dual career ladders are the following:

- They offer employees a career path in lieu of traditional promotions to supervisory or managerial positions.

- They can potentially reduce turnover among valued staff by providing expanded career opportunities and pay raises.

- If well managed, this type of program can encourage employees to continually develop their skills and enhance their value to the organization.

Dual career ladder programs are more common in scientific, medical, information technology and engineering fields, or in fields that typically exhibit one or more of the following characteristics:

- Substantial technical or professional training and expertise beyond the basic level.

- Rapid innovation.

- Credentials or licenses.

To be effective, a dual career ladder program must be well managed, as the program can become a “dumping ground” for lower-performing managers. Additionally, there may be resentment from employees not chosen for the program or from managers who feel the dual career employees are receiving similar pay as managers without the added burdens of supervising staff.

HORIZONTAL CAREER PATHS

The concept of horizontal career paths (also called “career lattices”) was introduced in many large organizations in the mid-to-late 1990s. In organizations with limited number of management and leadership positions, employees are encouraged to think of career paths both horizontally and vertically.

The potential benefits of formal horizontal career paths include the following:

- For a business with many distinct functions, employees can find challenging and rewarding work, broaden their skills, and contribute in new ways when they move laterally.

- For the organization, key positions can be filled with demonstrated performers.

- Horizontal paths can help employees who want to experiment in a related field. Structured programs also help employees quickly understand how their job fits into the overall success of the organization and how they can meet their professional goals at their current workplaces.

- Lateral career paths may help attract and retain employees from younger generations.

A career lattice strategy has to be understood by both managers and employees, and appropriate incentives need to be in place to reinforce the desired behavior. Organizations with successful lateral career programs share several common characteristics, including:

- Employee development is part of the culture and beyond training courses to include rotational assignments or temporary assignments in other functions, roles or locations.

- Compensation is not reduced from the current level, but employees in developmental roles may not receive the same bonuses or merit increases when making a lateral move. Well-developed competency models lay out the skills and experiences needed to be successful in more senior roles.

ACCELERATED AND “DIALED DOWN” CAREER PATHS

A few organizations have recognized that employees want a voice in tailoring their career paths to their life stages and as to whether they want to be on an accelerated path or a “dialed-down” path at a particular stage.

Some organizational projects require high intensity and others do not, but all are important to the organization. An employee who is in a stage of acceleration may have a better success rate on high-intensity projects, such as a mergers-and-acquisition project that requires a lot of hours and travel. On the other hand, if someone is in dial-down mode for personal reasons, then a lower intensity project would be a better fit.

In the accelerated or dialed-down career path model, the workload dimension should be indexed to compensation. Thus, if an employee has dialed down to 80 percent of the normal work time, the compensation should be lowered to 80 percent.

Implementing accelerated and dialed down career paths may result in:

- Improved employee satisfaction in career/life fit.

- Increased expectations for future satisfaction of career/life fit.

- Reduced stress knowing the option is available.

- Retention of top performers.

ENCORE CAREER PATHS

The concept of purpose-driven work in the second half of life has only recently become an issue. An encore career is the opportunity for an individual to do work that has a social impact after midlife work. Experts suggest that the impact of encore careers may be similar to that of women moving into the workforce in the 1960s and 1970s.

Many older workers not ready for full retirement are looking for jobs that can provide them with “means and meaning.” These individuals primarily have held professional and white-collar jobs, have at least a college education, often work 40 or more hours a week, and usually live in or near cities. This survey’s findings provide evidence of a growing social phenomenon that poses opportunities for nonprofits.

Many nonprofit organizations have traditionally relied on older individuals to perform volunteer or part-time work that came with only modest stipends. These opportunities will be less appealing as people live longer and traditional retirement plans disappear. HR functions in the nonprofit sector should consider adapting hiring policies to employees interested in encore careers. Moreover, nonprofit employers may want to reshape job descriptions to offer part-time and flexible work options, use online resources to make finding encore jobs easier, and provide education and training to meet new job requirements.

Career Paths Outside the Organization

In the last few decades, corporate restructuring and the recession have periodically resulted in the loss of hundreds of thousands of jobs in some industries, flatter organizations with less promotional potential and the creation of new types of jobs in other industries. These changes have led to the increase in the number of consultants and significant expansion of the “contingent workforce.”

CONSULTING

Large consulting organizations have been around for many years, and they have provided career ladders and promotional opportunities much the same as any other company. A new type of consultant has emerged, however, who has previously worked within the corporation. This exit from the organization can occur for a variety of reasons, including lifestyle and family considerations, lack of challenge and internal career progression, early retirement, corporate downsizing or personal choice.

Regardless of the reason, the independent consultant is someone who has expertise in a defined area and who markets that expertise to potential clients, primarily the previous employer. Generally, this type of consultant operates using a business model based on a limited size organization and in a limited geographic area. Although the consultant role itself may not provide a career ladder, the move from an organizational to a consultant role is a move on a career ladder that many people find both personally and financially satisfying.

CONTINGENT WORK

The “contingent workforce” includes individuals who work as temporary workers, contract workers or project workers. All these roles are designed to provide needed work to an organization for a limited time. The reasons people elect to pursue contingent work are as varied as the work settings in which the work is performed. Some people see it as a route to permanent full-time employment. For others, it is a lifestyle decision that allows them to work when they want for as long as they want. For still others, contract work provides variety and challenge as they move from worksite to worksite.

For the contingent worker, the traditional employer-employee relationship no longer exists, and people are self-employed in the sense that they control when, where and how they will work. This change in work patterns requires skills portability and lifelong learning as individuals are challenged to maintain their marketability in the business marketplace. From a career ladder perspective, individuals in the contingent workforce choose where they place their ladder. Although they have restricted ability to climb their ladder, they have made the choice that they would prefer to move their ladder from time to time rather than keep their ladder in one place and climb it.

Managers and HR professionals must be effective in their communications to employees about the organization’s career paths and career opportunities. Employers must handle conversations about the following potentially “tricky” topics carefully and honestly and without creating expectations or making commitments that the organization may not be able to fulfill:

- Gauging an employee’s interest in promotion without promising a specific job.

- Telling an employee he or she is a high-potential employee.

- Letting an employee know he or she is not considered a high-potential employee.

Employees should know how they are regarded so they can decide whether to go for a promotion when a job opens up. An individual should be given accurate and constructive information about the perception of his or her performance or readiness for particular roles.

Employers and HR professionals should be aware of potential legal issues that can arise in the context of career paths and career ladders, including gender stereotyping, discriminatory promotions and pay discrimination.

GENDER STEREOTYPING

Women sometimes face obstacles in the workplace because of gender stereotypes and a culture that rewards behavior and strategies used primarily by one gender. In addition to the risk of lawsuits or unwanted media attention, gender stereotyping may cause valuable talent to leave the organization in pursuit of other options.

Employers and HR professionals should consider questions that can shed light on women’s advancement opportunities in their organizations, including:

- Are the skills, knowledge and experience of recruits evaluated differently if the candidate is a woman or a man?

- How can or should individuals communicate their expectations, and how is this information collected so organizations can update their talent profiles to shape succession planning?

- How can talent management practices be redesigned to minimize the impact of gender and stereotypes of other protected groups on hiring, development, advancement and compensation decisions?

DISCRIMINATORY PROMOTIONS

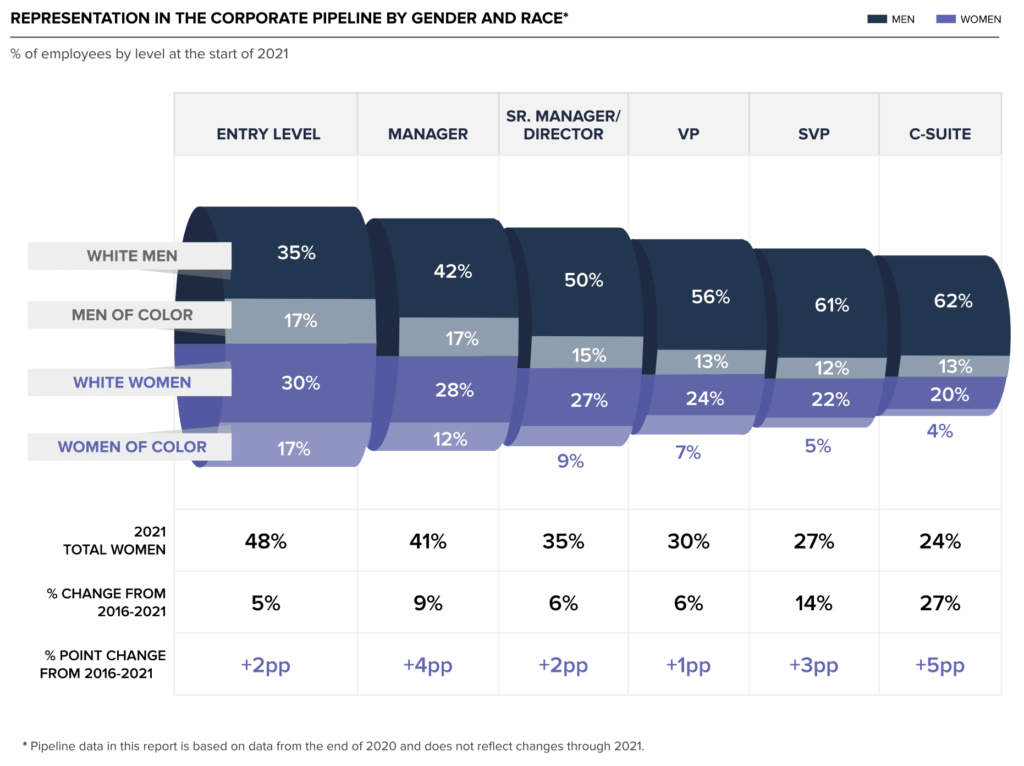

If not many women or minorities fill high-level positions in an organization, HR or legal counsel should look at the corporate ladder to see when a disproportionately lower representation of one gender or ethnicity occurs. This factor can be especially important if a company promotes from within because it would suggest that the underrepresented gender or ethnicity does not understand or have access to the organization’s career paths.

Lean In’s 2021 Women in the Workplace survey found significant underrepresentation of women in leadership.

To avoid discrimination lawsuits in promoting employees, employers need to have a reasonable rationale for every promotion. Moreover, employers should give careful consideration to how promotion opportunities are posted—specifically, whether to do it internally and externally at the same time. As with all HR policies, promotion policies and practices should be clear and consistent.

PAY DISCRIMINATION

If an employer’s positions have defined pay bands, then employees who are not promoted may reach the pay maximum for the job. Usually, women and minorities are paid approximately the same as others within similar positions, but there might be few minorities and women promoted to higher paying jobs.

Indicators of pay inequities between the pay for members of the majority group and members of other protected classes go beyond pay disparities in the same positions. Other tip-offs to potential pay discrimination may include:

- Significant turnover in a department.

- Retention that is significantly lower among minority groups or gender groups after one, two or three years.

- Equal Employment Opportunity Commission (EEOC) charges affecting a certain department.

- Significant differences from overall pay benchmarks at other employers.

One step to avoiding pay discrimination is to take a critical look at promotions. This should include a review of the rate of promotion for protected classes and the organization’s mechanism for providing information on promotions. EEO-1 reports can also be useful to determine underrepresentation of certain categories of employees.

HR professionals should analyze key metrics related to career progression programs to determine the return on investment (ROI) to the organization.

One way to calculate the ROI for career progression programs is to determine how these initiatives affect organizational turnover or retention rates and then to quantify their impact in financial terms. For example, an organization that has higher-than-average turnover rates for employees with three to five years of tenure with the firm may decide to develop individualized career maps as a way to boost retention. If the program reduces turnover rates, then the savings from replacement costs, such as recruiting, orientation and lost productivity, can be calculated.

The final step in calculating the ROI is to compare the cost of developing and implementing career progression initiatives in terms of staff time or consultant fees to the savings resulting from reduced turnover. To illustrate, if the cost of a career progression initiative was $45,000, but the efforts yielded a savings of $75,000 in turnover costs, then the ROI was $30,000.

Global HR professionals deal with many of the same talent management challenges as do domestic HR practitioners, but generally on a larger scale. Global research shows that individuals tend to stay with organizations that are seen as “talent-friendly” and progressive—that is, organizations with leading-edge work environments and people practices.

Global leveling—the process of systematically establishing the relative value of jobs and their corresponding pay ranges worldwide—is providing a framework for multinational organizations to implement talent and compensation management effectively across borders. The primary objectives for evaluating jobs and implementing a global grade structure are to support the development and career paths of employees and to facilitate the implementation of a global pay or rewards program.